|

This is the first lesson in a SERIES of lessons to cover POLYRHYTHMS. Polyrhythms are an advanced style of rhythm. If you do not have a basic understanding of rhythm already, this instructional series may be a bit over your head, and too difficult to understand. Even if you DO have a basic understanding of rhythm, polyrhythms are challenging to play and understand.

Several music examples will be used to demonstrate how to play and understand polyrhythms. But, first! What IS a polyrhythm? The word POLY means MANY. So, in simple terms, a polyrhythm means many rhythms. Steve Vai, in his paper called "Tempo Mental", says, "A polyrhythm is just what it says. Two rhythms, or “feels”, happening at the same time." However, it IS a bit more complicated than that. Why? Because if it were simply the case of having different "rhythms" being played at once, I would argue that most music is using polyrhythms. The drums, guitars, vocals, etc. are not all playing the exact same rhythm pattern all the time. However, this does not make a polyrhythm. A polyrhythm is used to create tension in a song. By placing at least two different rhythms together that sound somewhat "off" you can create something that really stands out to the listener's ear. When you see something like a triplet, or quintuplet, sextuplet, nonuplet, etc., you're probably dealing with a polyrhythm. Notes grouped in this fashion will have some indication that they are not naturally found within the given time signature you are playing in.

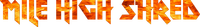

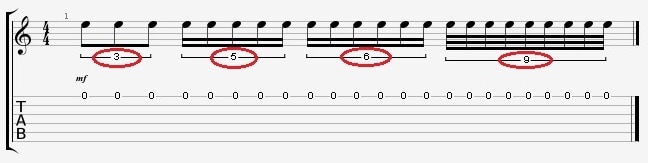

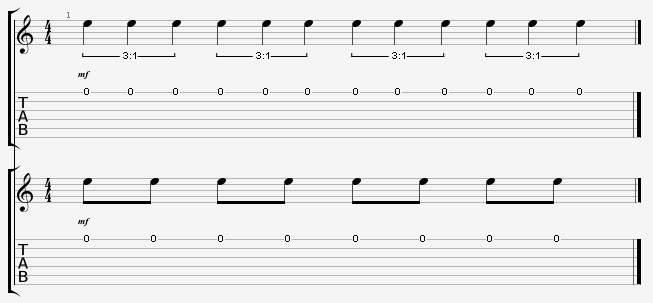

The circled numbers are indicating a deviation from what's normally found in this time signature. The numbers are telling you how to space these notes that would not occur, naturally, in the given time signature. You could also notate the same thing like this:

You would wind up hearing the same thing either way. There will be more information to explain what something like 5:2 means in a later lesson.

Now, beats are always evenly divided when dealing with note values that DO occur naturally in a given time signature. Most music you hear is in a 4/4 time signature. This means you have 4 beats that fill up the bar, or measure. Bar and measure are interchangeable, they mean the same thing. Now, the number up top in the time signature fraction is telling you how many beats fill up the bar. The number on the bottom is telling you the value of the beat. 4 equals a quarter note. You can have ANY number, ANY NUMBER on top. Doesn't matter. Go nuts! The only numbers you can have on the bottom are 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64, but good luck ever finding something with 64 on the bottom. Or even a 1. 1 = Whole note 2 = Half note 4 = Quarter note 8 = 8th note 16 = 16th note 32 = 32nd note 64 = 64th note So, why the hell am I telling you all this? Good question! This is to further explain dividing the beat(s) evenly. A whole note can be divided in half and give you a half note. A half note can be divided in half and give you a quarter note. Half of a quarter is an 8th note. Half of an 8th note is a 16th note. Half of a 16th note is a 32nd note. Half of a 32nd note is a 64th note. Another way to look at all that is this: A whole note = 2 half notes, or 4 quarter notes, or 8 8th notes, or 16 16th notes, etc. A half note = 2 quarter notes, or 4 8th notes, 8 16th notes, etc. A quarter note = 2 8th notes, or 4 16th notes, 8 32nd notes, etc. An 8th note = 2 16th notes, or 4 32nd notes, etc. etc. I hope that gets point across. None of this notation of rhythmic value will tell you to space 3 notes evenly over anything, unless you tweak things in order to make it happen. A triplet, the most common one being an 8th note triplet, is playing 3 evenly spaced notes over the time it takes to play 2 evenly spaced 8th notes.

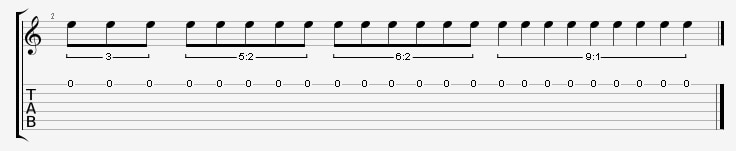

You could also notate the triplet like this and wind up with the same sound:

The ratio 3:1 is telling you that 3 notes are being evenly spaced over the time it takes for the one quarter note to be played. I don't think I've ever seen a ratio like this being used in a professional transcription. Usually, you'd see something more like 7:3. That means you are evenly spacing 7 notes over the time it takes to play 3 evenly spaced notes.

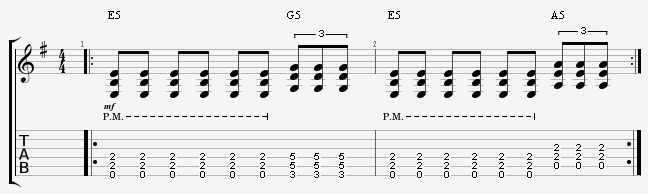

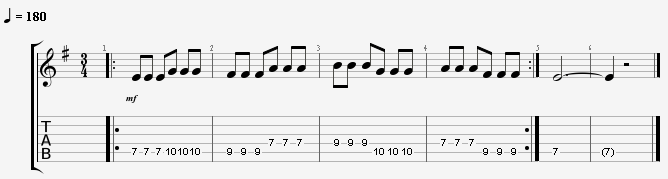

Now, you might be thinking, "but, John! I've heard and played plenty of music using triplets that doesn't sound like any tension is being made. You said a polyrhythm creates tension! Are you fucking stupid or something?!" Excellent point! Let's check out an example that uses 8th note triplets over just one beat.

Now, TO ME, throwing in one beat of triplets after playing 3 beats of straight 8th notes sounds a little jarring. It stands out. Tension was made. Now, let's do something similar with tripleted quarter notes.

I feel that playing quarter note triplets is more challenging than 8th note triplets. They feel and sound weird. You are playing 3 evenly spaced notes over 2 evenly spaced quarter notes when playing quarter note triplets. Technically, it's the same thing as playing 3 evenly spaced notes over 2 evenly spaced 8th notes. It's a 3:2 polyrhythm. 3 notes being played in the same time it takes to play 2 notes.

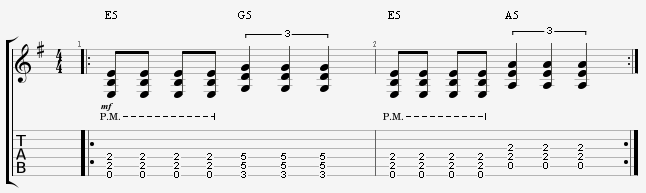

Now, for the sake of understanding all this, let's use a piece of music using only 8th note triplets.

When you listen to that in the video posted at the end of this blog entry, you'll hear how this example doesn't really sound like a polyrhythm. I would argue it's not a polyrhythm because both the guitar and drums are following a cohesive rhythm. The two instruments don't clash. No tension is present.

"Yeah, so what's your point?" My point is that something like this is normally notated differently. You could take the same piece of music and put it in a 3/4 time signature and get this:

When you listen to both versions of this example you'll hear that they sound the same. The cool thing about music is you can notate things differently to create the same outcome. It's all a big math equation.

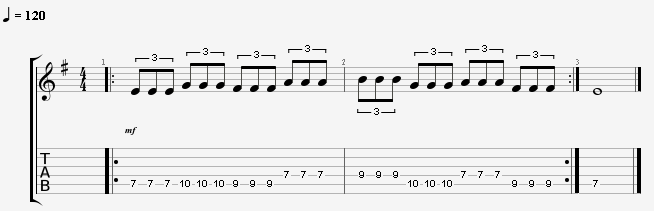

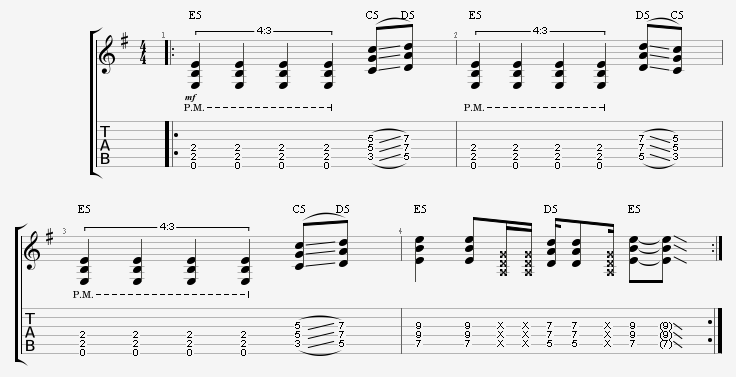

Playing a straight 8th note pattern in a 4/4 time signature at 120 bpm will be the same thing if you play the same notes at 180 bpm in a 3/4 time signature using straight 8th notes. A 3/4 time signature is telling you that 3 beats fill up the bar, and a quarter note gets the value of one beat. Using this time signature there is no longer a need to use triplet notation. There is no polyrhythm. And, it looks cleaner this way. Let's look at one last example of a polyrhythm before we start getting more in depth with everything. A commonly used polyrhythm is 4:3. This means you have 4 notes being played in the same time span 3 notes are played. Some choose to use this polyrhythm at the beginning of a bar to create tension, and then release that tension by playing something more in line with the given time signature. For example:

So far, polyrhythms have been demonstrated in just a part of the bar. Can you keep a polyrhythm going for multiple bars? Of course! That will be covered and demonstrated later on in this series.

Now, some people argue that a 4:3 polyrhythm, or 3:4 polyrhythm are polymeters. I believe they think, in the case of the 4:3 polyrhythm, a 4/4 time signature is being played over a 3/4 time signature. This same person may also say that in a 3:4 polyrhythm you have a 3/4 time signature being played over a 4/4 time signature. This isn't really the case. Polymeters indeed have two different time signatures being played simultaneously, but they have their own unique sound and parameters. The next video will be covering polymeters in depth. I feel it's best to get a good understanding of polymeters before moving on to in depth discussion and examples of polyrhythms. This is because I feel you'll have a much better chance of fully understanding what polyrhythms are, and how you can play them.

Want to help get more lessons like this made: CLICK HERE to see how!

photo credit: EJP Photo http://www.flickr.com/photos/29498428@N00/31609721381

One for the road via photopin https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/ photo credit: misterbisson http://www.flickr.com/photos/41894176272@N01/6509167963 butter via photopin https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

2 Comments

Ray McClain

9/14/2018 10:13:44 am

I happened, by chance, across Mile High Shared while trying to find an answer a question I had about Lydian chord progressions. WHAT TOOK ME SO LONG?!?!?!?!?!

Reply

John Taylor

9/14/2018 12:33:58 pm

Guess I'm just not a big enough name yet :)

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Available Instruction Courses

|

- Metal and Rock Guitar Lessons

- Reach Your Fastest Speeds

-

Menu

- Skype Lessons

- Sign Up for Skype Guitar Lessons

- Video Correspondence Lessons

- Sign Up for Video Correspondence Lessons

- FREE Lessons for a WEEK >

- Free Tabs

- Get TWO FREE eBooks

- Rates

- Instruction Courses >

- Video Feedback Lessons

- Contact

- Blog (LOTS of Free Lessons)

- Student Testimonies

- Backing Tracks

- Store

IN DEPTH

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed